A major part of learning how to eat intuitively is learning how to listen to your body. Your body is smart; it knows how to communicate its most basic needs: to breathe, to eat, and to sleep. Hunger is no different. It’s a natural physiological response that tells us it’s time to refuel our bodies with food. While many dancers are familiar with the typical signs of hunger, like a growling stomach or irritability, there are many subtle cues that often go unnoticed.

Subtle Signs of Hunger

Hunger won’t always present with a grumbling tummy or emptiness in your stomach. In fact, this can be considered a late stage of hunger— cues often missed only to end up ravenous. Every dancer’s hunger cues are unique, so staying attuned to your own body is essential. Recognizing these subtle signs of hunger is crucial as you learn to respond to them and eat, even if that means planning for emergency access to snacks.

#1: Simply having thoughts of food

For dancers who have done the work of dismantling food rules and healing their relationships with food, time can pass between meals and snacks when we’re not thinking about or wanting food. Contrary to this are thoughts about food— with or without sensations of physical hunger. In other words, simply wanting to eat can be an early sign that it’s time for a meal or snack.

#2: Relentless Fatigue

Feeling unusually tired even though you’ve had a good night’s sleep? It could be a sign that your energy reserves are running low. Missing meals and snacks can deplete glycogen and cause a subsequent drop in blood sugar.

#3: Recurring Headaches

A drop in blood sugar can also trigger headaches for dancers. Drinking water is a good start, but shouldn’t be used as a replacement for a snack or meal.

#4: Coldness

Hunger can make you feel cold, even when the temperature is comfortable. As your body attempts to conserve energy, it diverts blood away from the extremities, causing a feeling of chilliness.

#5: Mood Swings

Hunger can affect your mood and emotions. Irritability, mood swings, and increased stress levels can all be indicators that your body is in need of nourishment.

#6: Clammy Skin and Night Sweats

If you notice your skin feeling unusually clammy or sweaty, even in a cool environment, it may be a sign that your body is experiencing hunger-induced stress.

#7: Dizziness or Lightheadedness

A drop in blood sugar levels can cause dizziness or lightheadedness. If you stand up too quickly and feel a bit woozy, it might be due to hunger.

#8: Digestive Upset

Hunger can disrupt your digestive system, leading to stomach discomfort, cramps, or excessive gas. If you notice these symptoms, it may be your body’s way of telling you it’s time for a meal. Here’s an article to learn more about the connection between digestive health and the struggles that many dancers experience.

#9: Strange Body Hair

Lanugo is a fine layer of soft, downy hair that can develop on the body as a result of extreme weight loss and malnutrition. While it’s a natural response to the body’s attempt to conserve heat, dancers should understand that the presence of lanugo is often a red flag for more serious conditions like an eating disorder.

#10: Difficulty Concentrating

Have you ever found it challenging to focus on a combination or felt your attention wandering? When your body’s energy levels drop due to a lack of food, your brain struggles to maintain concentration.

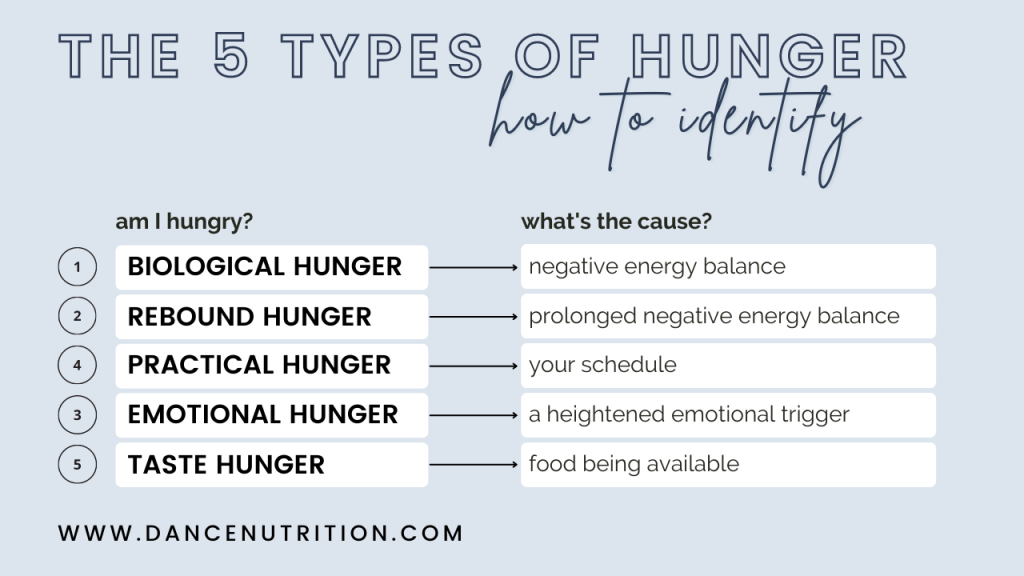

The 5 Types of Hunger

Hunger is far more complex than just a grumbling tummy. In fact, there are five different types of hunger that you can experience on any given day. The difference between each lies in the stimulus that sparks the desire to eat. Let’s break it down:

- Physical (or Biological) Hunger is what we most relate to “feeling hungry.” When physical hunger peaks, you might feel hunger pangs, stomach discomfort, a grumbling tummy, light-headedness, “hanger,” irritability, fatigue, and headaches. We’ll dive into more about physical hunger in just a bit. Stimulus to eat: negative energy balance.

- Rebound Hunger is a temporary phase that results from deprivation. During this phase, the body’s physical hunger cues may increase dramatically as it attempts to catch up after a calorie deficit. This phase can cause you to feel fearful of “letting go” of food rules. But as your body is fed consistently and adequately, it will rebuild trust in knowing that come tomorrow, it will no longer be deprived. From here, appetite cues eventually normalize. Stimulus to eat: chronic negative energy balance.

- Practical Hunger is especially important for dancers. This is eating in response to time constraints or a busy schedule. For example, if you’re navigating class and/or a long rehearsal, you may need to eat regardless of the presence of physical hunger cues. This will ensure that you’re not famished nor “hangry” later on. Another example would be eating dinner prior to a performance that will have you busy from 7-11 PM. You may not be fully hungry beforehand, but eating a balanced meal or snack will help to stabilize energy levels for the show. Stimulus to eat: your schedule.

- Emotional Hunger honors your emotional connection to food. It is very human (and normal) to desire food as an emotional coping mechanism. Food can offer comfort during times of intense emotional triggers like excitement, nervousness, anxiety/stress, and sadness/loneliness. Emotional eating, as a cultural construct, is often associated with negative implications. But there is no shame in having an emotional connection to food. If you feel that emotional eating is problematic, then you may need to consider whether or not deprivation is also playing a role and how to build additional coping mechanisms to navigate emotional triggers. To learn more about emotional eating, read this article. Stimulus to eat: heightened emotions (either positive or negative).

- Taste Hunger involves eating food just because, well, you like it! Food plays a major role in celebrations, holidays, cultural traditions, and social settings. Let’s say, for example, you’re at a dinner party with friends. Though you’re physically full from the meal, dessert arrives, and that brownie parks itself in front of you. As your friends dive into the dish, you too, pick up your fork and join the fun. In this instance, you’re satisfying your taste hunger. This is also an example of how intuitive eating differs from the “eat when hungry stop when full” diet. To learn more about taste hunger and its role in mealtime satisfaction, read this article. Stimulus to eat: food being available.

Appetite Dysregulation: What happens when you ignore hunger?

For those recovering from an eating disorder, navigating a history of severe dieting, or experiencing consistent food insecurity, it can be challenging to rely solely on physical hunger cues. This is because physical hunger can temporarily diminish in the presence of chronic food restriction.

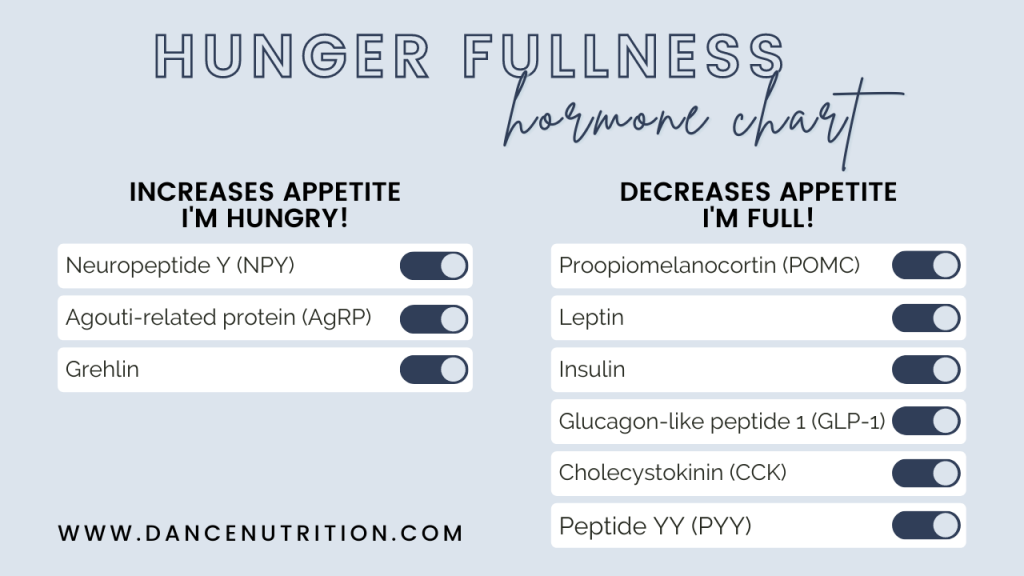

Hormones, specifically leptin (the “feel full” hormone) and ghrelin (the “feel hungry” hormone) regulate your day-to-day hunger and fullness as a means to maintain energy balance. In fact, there are several additional appetite-regulating hormones that play a role in hunger and fullness (see below).

When not consistently responding to hunger, the body eventually experiences appetite dysregulation. For some, this means an overall lack of hunger— a drive in restrictive eating is especially common in dancers with a history of anorexia nervosa. For others, however, an increase in hunger can occur— a spike in hunger hormones, a plummet of fullness hormones, and an increased reward response to food. You’ll also put yourself at risk for the development of RED-S. Bottom line: ignoring hunger imbalances your hormones and dysregulates your appetite.

A Dancer’s Guide to Hunger and Fullness

In addition to these hormonal shifts, external factors like busy schedules and messaging from diet culture can further impede our mealtime decisions. “Clean” eating or the pursuit of “wellness” often comes with a supposed degree of “control” around food. Ironically, the more we attempt to control our hunger and satiety cues, the more out of control we become around food.

Learning how to reconnect with your innate feelings of hunger (and fullness) is critical for building a supportive relationship with food. This is especially true for intuitive eaters, who learn how to disconnect those external messages to reconnect to internal communication. Now that we’ve uncovered how to identify your hunger, let’s unravel how to respond to it.

#1: Eat Consistently

Eating enough calories throughout your day, along with eating consistently (every 2-4 hours), helps to keep this hormonal communication in line. Create a flexible meal plan that incorporates a meal and/or snack every 2-4 hours or depending on your schedule. Hunger aside, this plan will help you regain the ability to feel hunger appropriately.

#2: Say “Bye!” to Unnecessary External Cues

From calorie counts and macros to restrictive food rules and My Fitness Pal, there are many methods available to control our food intake. With the exception of the flexible meal plan discussed above, steer clear of these external reasons for eating. Instead of relying on your meal’s calorie allowance, check in mid-meal. Ask yourself: “At this point, will I feel energized and satisfied for the next few hours?” Create a balanced situation and eat enough. These are two critical considerations as you attempt to answer that question.

#3: Prioritize the Type of Hunger You’re Experiencing

Now that you’ve removed those restrictive rules and are fueling your day sufficiently, it’s time to consider when and how to assess your hunger and fullness. First, it’s not always practical to rely on your physical hunger cues. For dancers especially, physical movement naturally blunts physical hunger. Before you know it, a day of rehearsals can translate to hours without an ounce of hunger. As a result, you’ll need to prioritize practical hunger and assess when you can rely on your flexible meal plan. On your days off, however, take advantage of your ability to check in with physical hunger cues.

Just a note: it’s also okay if an eating experience does not feel so great or live up to your expectations. In this instance, prioritizing biological hunger (or rebound hunger in the case of healing from deprivation) is more important than prioritizing taste hunger or satisfaction.

#4: Use the Hunger/Fullness Scale

Now let’s talk about that hunger/fullness scale. As you start the process, realize that it’s common to be familiar with the extremes of the scale: extreme hunger and extreme fullness. Utilize each meal, when possible, to assess. You’re likely to start feeling hunger in your stomach, but you can also feel hunger in your head with lightheadedness and mood swings being a strong sign of extreme hunger. Prepare balanced snacks to avoid these instances. When it comes to your actual eating experience, assess your fullness and satisfaction. Revert back to that question, “At this point, will I feel energized and satisfied for the next few hours?”

If you want a bit more help, then be sure to check out my program, The Healthy Dancer®, where we dive into the nitty-gritty of utilizing the hunger/fullness scale. PS- snag my free guide to navigate your meals and snacks.