Carbohydrates, protein, and fat—the three macronutrients of a dancer’s fuel mix offer the necessary components needed to support a demanding dance schedule. But there’s another mealtime component often overlooked: fiber.

Understanding the role fiber plays in your meal plan can be helpful— but like many aspects of nutrition, it’s possible to have too much of a good thing. In this blog post, we will explore the importance of fiber how to maximize its benefits effectively.

What is Fiber?

Dietary fiber is a type of carbohydrate— a starch— found in plant foods like fruits, vegetables, grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds. The 2016 FDA Nutrition and Supplement Facts Label Final Rule established the following definition for the term “dietary fiber:” Fibers [in food] with evidence of a beneficial physiological effect on human health.

Unlike other carbs, fiber isn’t broken down into sugar but instead resists digestion, passing through the digestive tract relatively intact. Dietary fiber comes in two forms: soluble and insoluble. The difference is simple: soluble fiber dissolves in water, whereas insoluble fiber does not. Each type of fiber plays a unique role in the body:

Soluble vs. Insoluble Fiber—What’s the Difference?

Soluble Fiber

Soluble fiber absorbs water while it moves through the intestinal tract, forming a gel-like substance (like a sponge). This unique characteristic slows the movement of food, allowing for the regulation of blood sugar. The result is a sustained release of energy— especially helpful when moving through a day of classes and rehearsals. This effect on digestion also contributes to feelings of fullness, and increases a meal’s staying power.

Another benefit of soluble fiber is its ability to bind with bile acids in the small intestine, removing them from the body. The loss of bile acids stimulates the liver to utilize cholesterol to replenish that bile acid supply. This reduces LDL (AKA “bad”) cholesterol. Sources of soluble fiber include oats, chia, legumes (peas, beans, lentils), flax, vegetables, apples, and/or citrus fruits.

Insoluble Fiber

Insoluble fiber does not absorb water and thus adds bulk to 💩. This speeds the movement of digestive waste, allowing for regular bowel movements. Insoluble fiber also promotes gut health via prebiotic fermentation. Sources include plant foods with edible peels or seeds (think apples, cucumbers, figs, etc.), whole grains, corn, whole wheat bread products, cauliflower, potatoes, nuts, and green beans.

Which is best?

Most plant foods contain a mixture of both fibers, so no need to obsess about which fibers are coming from specific foods. Aside from the benefits mentioned above, both soluble and insoluble fibers contribute to appetite regulation, and aid in disease prevention (lowering the risks of breast cancer, colorectal cancer, the onset of Type 2 Diabetes, and even heart disease).

Fiber and Digestive Health

One of the most well-known benefits of fiber is its role in maintaining digestive regularity— adding bulk to speed the transit of digestive waste (💩) for elimination (🚽)— especially helpful for those who struggle with constipation.

Additionally, indigestible fibers are fermented in the colon, contributing to the production of byproducts that nourish the gut microbiome. Soluble fibers are fermented during digestion, providing prebiotic nourishment for gut bacteria.

How much fiber does a dancer need?

Daily fiber needs vary with age— 25-40 grams being the general range. It’s known that the general American population only consumes about 15 grams of fiber per day, but with popular diets like “clean” eating, many dancers surpass their maximum fiber needs.

To assess how much fiber you’re getting in a day, we must first break down the various sources of fiber in your diet. As mentioned earlier, “dietary fiber” includes naturally occurring intact fibers. However, the FDA allows for this definition to include several processed fibers (those extracted from plant sources and added to various foods).

Intact Fibers are considered “intact” because they have not been removed from their source and rather, are naturally occurring. Vegetables, whole grains, fruits, cereal bran, flaked cereal, and flour are examples. Sufficient research supports the health benefits of intact fibers.

Processed or Functional Fibers (sometimes referred to as isolated fibers) are used to fortify foods that are not naturally high in fiber (think about yogurts and other non-plant foods). Isolated fibers that you might spot on labels include Beta-glucan, Psyllium husk, Cellulose, Guar gum, Pectin, Locust bean gum, and Inulin. You’ll also find these used in fiber supplements, powders, and tablets. These isolated fibers offer some of the same benefits of naturally occurring fibers, but research supporting long-term use is limited. Furthermore, these fibers lack the additional nutrients found in naturally occurring fibrous foods.

Is it possible to eat too much fiber?

With isolated fibers easily accessible throughout today’s food supply, it is possible to go overboard. The same holds for “clean” eating lifestyles that often drive a fixation on *whole* foods.

There is no tolerable limit set for fiber, so quantifying a maximum requirement is challenging. For some, excessive intake of fiber can result in negative consequences like bloating, excess gas, stomach discomfort, constipation, diarrhea, and loss of appetite. An excessively high-fiber diet may also negatively impact ovulation and ultimately, exacerbate hormonal imbalances.

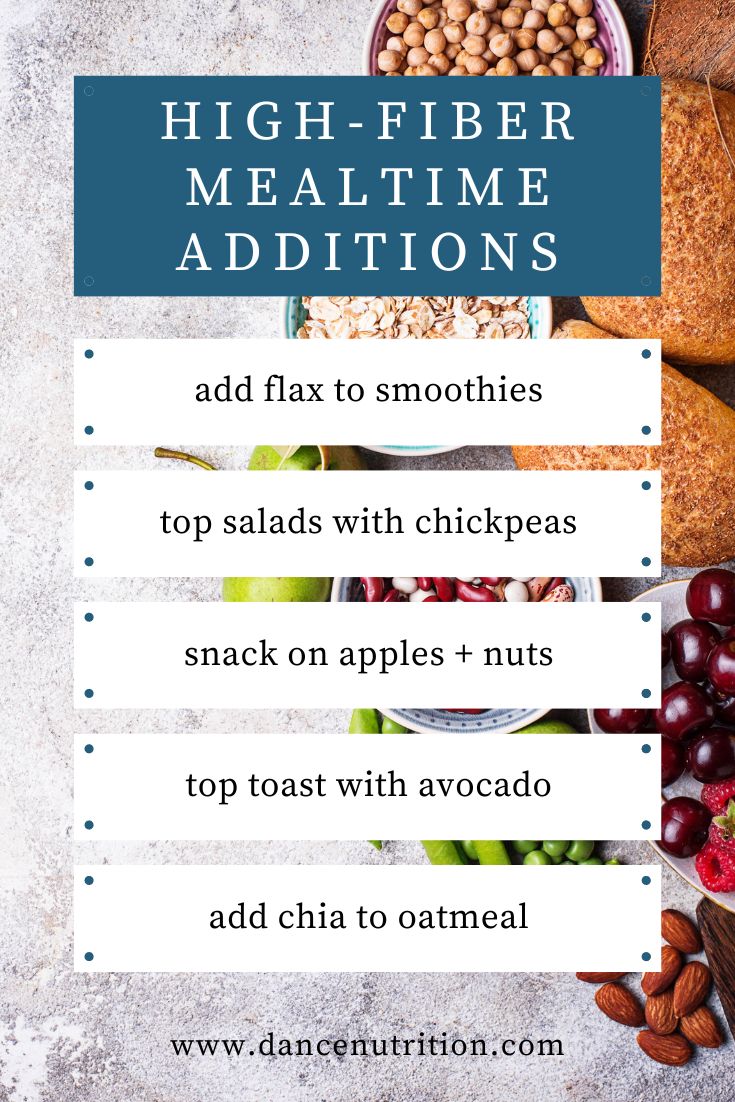

I encourage a food-first approach as a more economical route. Aim to include fibrous foods throughout your daily meal plan— nuts, seeds, legumes, and veggies. To learn more about plant-based foods, check out this article and consider these tips to increase your fiber intake:

- Choose whole grains and whole-grain bread products over refined versions.

- Increase plant-based meals (eggplant lasagna, bean burgers, bean pasta).

- Add fruit, popcorn, nuts, seeds, and whole-grain crackers to snacks.

- Add extra veggies with meals.

- Include fibrous foods throughout your week (split peas, figs, peas, lentils).

Can fiber help me in the bathroom?

The role of dietary fiber on digestive regularity is well understood in research. Assess your tolerance to a high-fiber diet. If you’re struggling with diarrhea, add sources of soluble fiber to your meals. This will help to absorb some of that excess water. On the flip side, if you’re struggling with constipation, add sources higher in insoluble fiber to move things along (however, you’ll need to up your water intake as well!) Most importantly, consult with a Registered Dietitian Nutritionist to better identify meal- and snack- opportunities to add fiber without going overboard.

Fiber for weight loss?

Diets high in fiber are known to promote satiety between meals, making you less likely to feel famished going into your next meal. However, be wary of the “let me fill up on fiber to eat less” mentality. This, along with filling up on high-fiber options to “dodge” cravings can easily result in a cycle of compensatory eating and an overall unsupportive relationship with food. You’ll also risk feeling too full for meals and snacks that offer a variety of other key nutrients. Check out these articles to learn more about this:

Key Takeaways

It’s easy to fixate on the numbers (ie. grams of fiber). But this fixation can cycle into disordered eating territory. Include fibrous foods throughout your day, however, don’t obsess. Think about how your meals and snacks make you feel. If you feel energized after adding fibrous whole-grain bread to your lunch, then go for it! If you’re experiencing excess gas after eating a salad, then hold off on the raw veggies (especially before dancing). Aim for a food-first approach with complex carbohydrates being part of it (learn more about these sources here!). Here are some tips to ensure you’re getting enough fiber without overdoing it:

- If you’re currently not eating much fiber, increase your intake slowly. This allows your digestive system to adjust and can help minimize any discomfort.

- Drink plenty of water to help fiber move smoothly through your digestive system and prevent constipation.

- Aim to get your fiber from a variety of plant-based foods, including fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, and seeds. This not only provides fiber but also ensures you’re getting a range of other essential nutrients.

- Pay attention to how your body responds to changes in fiber intake. If you experience discomfort, it may be worth adjusting your intake or consulting with a licensed Registered Dietitian Nutritionist.