Using oil as a cooking medium or ingredient isn’t an uncommon practice for dancers—in fact, I’ve encouraged it as a fabulous source of unsaturated fats (the type we consider to be “heart healthy”) for years. But recently, cooking oils have received a ton of criticism. In this article, we’ll uncover the claims and debunk the fears surrounding this nourishing mealtime addition.

The chemistry of seed oils

Generally, edible oils are vegetable oils—this includes seed oils. Common examples are olive, canola, grapeseed, avocado, coconut, soybean, palm, corn, flax, safflower, and a variety of nut oils. In order to extract the oil from the seed, a variety of processing techniques can be used.

Refined oils are those that have been made using heat (expeller-pressed) and/or extracted using chemical solvents— like hexane. Refined oils are not only bleached (to remove the color) and deodorized (to remove the taste and smell), they’re sometimes chemically altered to withstand high-heat cooking methods like frying.

Unrefined oils are most commonly made by cold-pressed methods. Oil extraction occurs from the grinding and milling of the seeds, without the use of heat. Cold-pressed oils are more expensive to both produce and purchase. They’re also known to retain more of their antioxidative properties and when compared to refined oils, they retain their unique flavor and smell.

Why the seed oil confusion?

For starters, words like “refined,” “bleached” and “deodorized” feed a rhetoric that undeniably blacklists *processed food.* As a result, refined oils are often the target of backlash with refinement practices (particularly those involving chemical solvents) taking much of the blame. But according to food scientists, inconsequential amounts of these solvents end up in the final product. There is also no evidence to support any risk or danger from the consumption of foods containing trace residual concentrations of hexane, a commonly used solvent. In fact, the average consumer ingests more hexane from inhaling car fumes than from the minute amount in food. The bottom line? The trace amounts of hexane that may end up in our food supply aren’t worth stressing over— especially if it’s spiraling into food anxiety.

What are the benefits of seed oils?

Before we discuss the benefits, let’s review the basics of dietary fats (AKA the fat found in food). Dietary fats vary in their chemical makeup— these characteristics help us classify them:

- Saturated fats are naturally found in animal products like butter and whole milk dairy.

- Unsaturated fats are naturally found in plant foods and can be further categorized into monounsaturated fats and polyunsaturated fats.

- Trans fat is a product of food processing (but also found naturally in trace amounts of some foods). While trans fats have been associated with an increased risk of heart disease, they’ve also been removed from our food supply since 2018– so worrying about trace amounts, even those from partially hydrogenated oils, isn’t worth it.

I’ve previously unpacked much of the confusion surrounding dietary fat— for the purpose of this article, we’ll focus on those predominate in cooking oils: unsaturated fats.

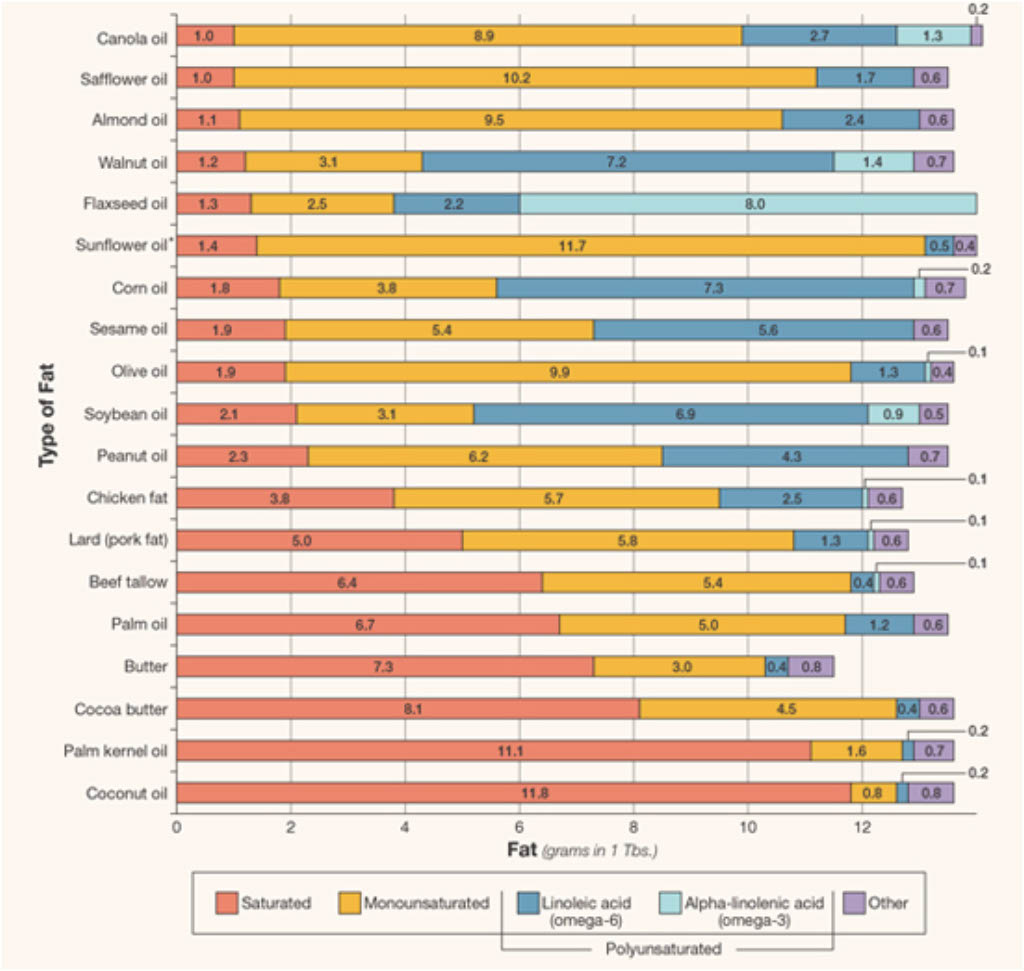

Monounsaturated (MUFAs) and polyunsaturated fats (omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs) are abundant in plant-based foods like nuts, seeds, olives, and avocados. They’re also abundant in some species of fish like salmon and tuna. Foods rich in unsaturated fats contain a mixture of these fatty acids. Here’s an image that demonstrates the various concentrations of fats in certain oils (side note: this is a super old image from CSPI… funny thing is it doesn’t even include avocado oil— likely because it wasn’t a trend yet!)

My reason for sharing this isn’t to lead you into a tunnel of “which is the *healthiest* oil.” Rather, it’s to demonstrate the importance of zooming out— detangling much of the fears around dietary fats requires us to utilize a wide-lens approach. From the research, we know that diets rich in polyunsaturated fats—especially when replacing some sources of saturated fats— have been associated with reductions in blood cholesterol and a reduced overall risk of heart disease. Looking at this chart, we can see that even those more *processed* seed oils— soybean, corn, and canola— contain an abundance of these heart-healthy fats.

In addition to heart-healthy unsaturated fats, seed oils contain a range of beneficial compounds like phytosterols and polyphenols— both have been associated with reducing inflammation. They’re also packed with essential vitamins and minerals, particularly vitamin E, a powerful antioxidant. Quick recap: a degree of oxidative stress is normal in the human body. Excessive amounts have been associated with the signs of disease. Antioxidants like vitamin E and vitamin C are defenders of this stress.

Aren’t omega-6 fats pro-inflammatory?

Currently, there is no evidence that supports the claim that omega-6 fatty acids induce inflammatory effects in humans. In fact, a review of the literature further suggests that consumption of omega-6 fatty acids (the most common in the Western diet is linolenic acid) does not increase the amount of pro-inflammatory precursors (ie. arachidonic acid) in the blood (don’t forget… when replacing saturated fat, omega-6 polyunsaturated fats support heart health).

Another review of the literature disputes the claim that polyunsaturated fat, particularly omega-6 linoleic acid, is pro-inflammatory. And last, this review from 2017 challenges the assumption that a higher omega 6-to-omega 3 ratio is harmful to health. Here’s a fantastic article that dives deeper into the pseudoscience surrounding seed oils and associated polyunsaturated fats. Food Science Babe also debunks these fears, among others, at length.

Cooking oils

The key advantage of oils is their versatility in the kitchen— allowing us to incorporate them seamlessly into our daily meals, and enjoy their health benefits, without compromising the taste of our dishes. But there are speculations surrounding whether some oils are safer to cook with than others.

It is true that different oils react differently to heat. When overheated, oils break down, producing polar compounds that may be harmful to health. A 2018 study found that oils predominant in saturated fats (ie. butter, coconut oil) and monounsaturated fats (ie. extra virgin olive oil) are most heat stable, while those predominate in polyunsaturated fats (canola, vegetable, grapeseed) are less heat stable. This goes against popular opinion, which suggests that we should utilize an oil’s smoke point to determine whether or not it’s best for cooking. In fact, the researchers concluded that oils with the highest smoke points – canola, sunflower, and grapeseed – produced the highest levels of harmful compounds when overheated. Here’s a great article that speaks more on the topic.

With all this said, limitations of this study exist. First, the oils tested were heated alone and according to the authors, “…the absence of food… may have allowed for a greater impact of oil oxidation.” Another consideration is the presence of antioxidants (vitamin E is most potent in extra virgin olive oil). This potency might help to explain the lowered rate of oil degradation.

What’s the best oil to cook with?

Despite these newer findings, it’s important to consider the practicality of these results through a wider lens. First, are you burning your oil before cooking with it? Likely no. In fact, many home-cooking methods won’t reach temperatures that risk severe degradation of oil. If you are deep frying, avoid recycling your oil over time (those harmful compounds can build up). Last, patterns over time always matter, and variety is key when it comes to nutrition. A few considerations:

- For frying, choose an oil with a high smoke point (see below). Refined oils, avocado oil, safflower oil, and vegetable oil are examples. Don’t reuse the oil.

- For baking, aim for a neutral-tasting oil like avocado or vegetable oil as these won’t alter the flavor of your finished product.

- For sautéing or searing, try a flavorful oil (ie. extra-virgin olive oil or avocado oil)— these may produce the least amount of polar compounds when heated.

- For raw salads, a flavorful dressing (I prefer extra virgin olive oil). Since the oil isn’t being heated, the smoke point doesn’t matter. Choosing an unrefined oil will be richer in antioxidants.

The bottom line? Choose the cooking medium that is most accessible to you and preferred from a taste perspective. Personally, I keep a few on hand— extra virgin olive oil for salads and marinades, vegetable oil, avocado oil, and coconut oil for baking, and olive oil for sautéing. Might this risk a few polar compounds in my scrambled eggs or stir fry? Maybe. But over-analyzing, stressing, and experiencing food anxiety will impose more implications on my health. I’m also a fan of butter. While it’s high in saturated fat, it offers a very satisfying flavor and mouthfeel (a priority of food flexibility).